The postpartum period can be a chaotic time for many women. Right after birth, women experience an abrupt decline in their estrogen and progesterone levels which are known to help regulate mood states. As a result, many new mothers are susceptible to drastic mood changes during this period. Their risk for postpartum psychiatric issues can dramatically increase when dealing with stressful life events, interpersonal problems, an infant with health issues, a prior history of depression, family history of depression, an unplanned pregnancy, and/or poor social support.

Sunday, March 30, 2014

“Baby Blues”: What Every Internist Should Know About Postpartum Psychiatric Dx

Internal Medicine Board Review: Ring-Enhancing and Non-Enhancing Lesions

A favorite of the USMLE Steps, NBME Internal Medicine Shelf, and ABIM Internal Medicine Board Exams seems to be those ring-shaped lesions picked up on imaging studies. Often, the scenario is a ring lesion identified on a CT head scan in an immunocompromised patient (particularly one with HIV or AIDS). These can be challenging because the clinical vignette focuses on the description of the lesion without providing detailed serologies. So let’s use an efficient approach to identifying the most commonly encountered ring lesion etiologies on medical exams.

The first step is to determine whether the lesion presented on the CT scan is ring-enhancing or non-enhancing.

If it is a ring-enhancing lesion, the most commonly seen etiologies are

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis (50%)

- Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (30%)

- Less commonly, Bacterial or Fungal abscess (e.g. Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Aspergillosis, Tuberculosis and Trypanosomiasis)

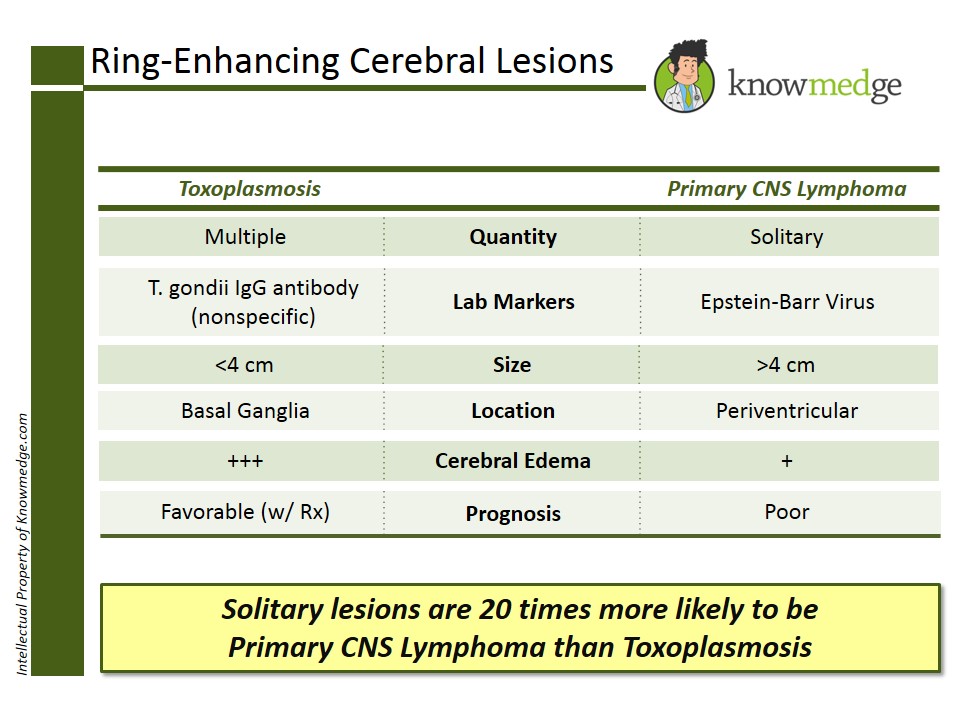

Cerebral Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of ring-enhancing cerebral lesions. Often, multiple lesions are seen, usually located in the basal ganglia. It is unlikely to be seen in a patient who is already receiving prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). Patients with AIDS and CD4 count less than 100/microL are at increased risk. It’s very important to remember that Toxoplasmosis serologies are non-specific but patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis are seropositive for T. gondii IgG antibody.

Primary CNS Lymphoma is the second most common cause of a ring-enhancing cerebral lesion. Unlike cerebral toxoplasmosis, primary CNS lymphoma may be solitary. Thus, if a solitary lesion is detected, even if toxoplasma serology is positive, CNS lymphoma is the more likely diagnosis than toxoplasmosis. The location of CNS lymphoma is more commonly in the periventricular areas. Lesions greater than 4cm in diameter are more likely to be primary CNS lymphoma rather than cerebral toxoplasmosis. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is quite specific for primary CNS lymphoma.

And the ring non-enhancing lesions are typically due to…

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML), which is attributed to the JC virus. It presents with multiple demyelinating lesions. It predominantly affects the white cerebral matter, in particular the brainstem and the cerebellum. Other patients at risk of developing PML are those receiving natalizumab therapy for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, efalizumab for psoriasis, and brentuximab for Hogkin’s lymphoma.

I hope you find this review helpful in rapidly identifying the cause of each brain-ring lesion you may encounter on the USMLE Steps, NBME Internal Medicine Shelf, and ABIM Internal Medicine Board Exams.

Thursday, March 27, 2014

Internal Medicine Board Review: Ring-Enhancing and Non-Enhancing Lesions

A favorite of the USMLE Steps, NBME Internal Medicine Shelf, and ABIM Internal Medicine Board Exams seems to be those ring-shaped lesions picked up on imaging studies. Often, the scenario is a ring lesion identified on a CT head scan in an immunocompromised patient (particularly one with HIV or AIDS). These can be challenging because the clinical vignette focuses on the description of the lesion without providing detailed serologies. So let’s use an efficient approach to identifying the most commonly encountered ring lesion etiologies on medical exams.

A favorite of the USMLE Steps, NBME Internal Medicine Shelf, and ABIM Internal Medicine Board Exams seems to be those ring-shaped lesions picked up on imaging studies. Often, the scenario is a ring lesion identified on a CT head scan in an immunocompromised patient (particularly one with HIV or AIDS). These can be challenging because the clinical vignette focuses on the description of the lesion without providing detailed serologies. So let’s use an efficient approach to identifying the most commonly encountered ring lesion etiologies on medical exams.

The first step is to determine whether the lesion presented on the CT scan is ring-enhancing or non-enhancing.

If it is a ring-enhancing lesion, the most commonly seen etiologies are

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis (50%)

- Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (30%)

- Less commonly, Bacterial or Fungal abscess (e.g. Cryptococcosis, Histoplasmosis, Aspergillosis, Tuberculosis and Trypanosomiasis)

Cerebral Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of ring-enhancing cerebral lesions. Often, multiple lesions are seen, usually located in the basal ganglia. It is unlikely to be seen in a patient who is already receiving prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). Patients with AIDS and CD4 count less than 100/microL are at increased risk. It’s very important to remember that Toxoplasmosis serologies are non-specific but patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis are seropositive for T. gondii IgG antibody.

Primary CNS Lymphoma is the second most common cause of a ring-enhancing cerebral lesion. Unlike cerebral toxoplasmosis, primary CNS lymphoma may be solitary. Thus, if a solitary lesion is detected, even if toxoplasma serology is positive, CNS lymphoma is the more likely diagnosis than toxoplasmosis. The location of CNS lymphoma is more commonly in the periventricular areas. Lesions greater than 4cm in diameter are more likely to be primary CNS lymphoma rather than cerebral toxoplasmosis. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is quite specific for primary CNS lymphoma.

And the ring non-enhancing lesions are typically due to…

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML), which is attributed to the JC virus. It presents with multiple demyelinating lesions. It predominantly affects the white cerebral matter, in particular the brainstem and the cerebellum. Other patients at risk of developing PML are those receiving natalizumab therapy for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, efalizumab for psoriasis, and brentuximab for Hogkin’s lymphoma.

I hope you find this review helpful in rapidly identifying the cause of each brain-ring lesion you may encounter on the USMLE Steps, NBME Internal Medicine Shelf, and ABIM Internal Medicine Board Exams.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)